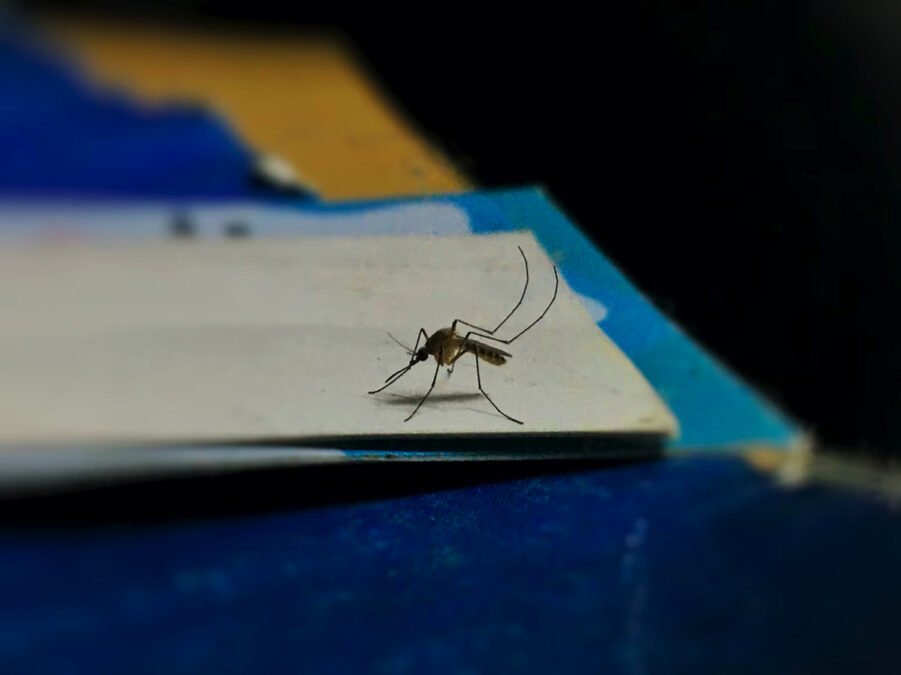

According to the CDC, mosquitoes that carry and spread the West Nile virus are becoming resistant to theinsecticides that communities use in mass sprays to kill them and their eggs.

The more-resistant mosquitoes are from the species called Culex and according to Roxanne Connelly, a medical entomologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a major issue in the United States.

“It’s not a good sign,” Connelly said. “We’re losing some of our tools that we normally rely on to control infected mosquitoes.”

This is coming after the U.S. had its first case of malaria in two decades, after five people that did not have any recent international travel history fell sick.

The increasing mosquito population is thought to be brought about by higher rainfall, melting snowpacks, and intense heat waves.

Connelly and his team conducted a research at the CDC’s insect lab located in Fort Collins, Colorado, which houses tens of thousands of mosquitoes, and discovered that Culex mosquitoes are living longer when they’re exposed to insecticides.

“You want a product that’s gonna be able to knock them down, not do this,” Connelly said, pointing to a bottle of mosquitoes exposed to the insecticide and many of them were still flying.

Connelly research however showed that the mosquitoes are not yet resistant to the regular insecticides used commercially in homes and while hiking or other outdoor activities.

According to the CDC, there have been 69 human cases of West Nile in the U.S., so far this year. The record number was 9,862 cases in 2003.

However, as West Nile cases usually tend to peak in August and September, there is a higher chance that more people will be bitten and fall sick.

“This is just the beginning of when we see West Nile start to take off in the United States,” said Dr. Erin Staples, a medical epidemiologist at the CDC’s Fort Collins lab. “We expect a steady increase of disease cases to occur over the next several weeks.”

In Maricopa County, Arizona, 149 mosquito traps have tested positive for West Nile so far this year, compared with eight in 2022.

John Townsend, manager of Maricopa County’s Vector Control Division of Environmental Services, noted that heavy rainfall created many pockets of standing water, which when coupled with heat, is the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes.

“The water that is sitting there is just ripe for mosquitoes to lay eggs in it,” Townsend said. Mosquitoes hatch more quickly in warmer water — within three or four days, he said, — compared with up to two weeks when they’re in cooler water.

An unusually rainy June in Larimer County, Colorado — where the Fort Collins lab is based — has also led to an “unprecedented abundance” of mosquitoes that can spread West Nile, said Tom Gonzales, the county’s public health director.

The County data showed that the number of mosquitoes that can spread West Nile this year increased by five times, compared to the previous year’s figure.

The increases in certain areas of the country are “very concerning,” said Connelly. “This is something different than what we’ve been seeing for the past few years.”

Symptoms of West Nile virus

According to theCDC, the majority of infected people did not show any symptoms, and one in five experienced a fever, headache, body aches, vomiting, and diarrhea.

One person out of 150 people infected with West Nile virus will have serious complications, including death. Though anyone can become severely ill, those over the age of 60 and those with underlying medical problems are at higher risk.

There is also no treatment or vaccine.

West Nile virus does not spread from person to person through casual contact, but only by Culex mosquitoes. The insects become infected when they bite sick birds, then they spread the virus to people through another bite.

West Nile was first detected in the United States in 1999, and with several thousands of people getting infected, it became the most common mosquito-borne illness.